I’m white.

I have never understood what it is like to be an African-American.

Or Latino. Or Asian. Or Indian.

The truth is, I will never fully understand what it’s like to be anything but white.

So I have to make an intentional effort to understand what it’s like to be an ethnic minority in the U.S.

But I’m starting to understand what it’s like to not be white. I’m trying.

Why? Because I’m learning ethnic empathy.

Merriam-Webster defines the word empathy as “the feeling that you understand and share another person’s experiences and emotions.”

To empathize is to imagine yourself in another person’s circumstances—to “feel in” with them.

I’m learning empathy. Just a few years ago, I would have rolled my eyes to hear complaints of racial injustices.

“The civil rights movement was needed in the ’60s. But things are better now. Right?”

Now I realize that’s a naive answer. Racism is real. I see it, and I hate it.

So what changed me? I moved from rural Ohio to Atlanta, Georgia, one of the most diverse cities in America.

I attended Killian Hill Christian School—a school that is only one-third white.

For the first time in my life, I wasn’t in the majority.

For the first time in my life I talked, laughed and studied with amazing people who happened to be black, Asian or Hispanic.

I sang in choir and played sports with an astonishingly diverse group—my best friends. But when we left the safety of our private Christian school, racism was evident.

People didn’t always speak racism. But we saw it, felt it in the untrusting stares and stiffened body language.

It was cold. It was raw. And it changed me, or at least started the process of change. It helped me empathize.

Empathy is essential. But how does it work? How can you learn to share someone’s experiences and emotions? I have two suggestions.

First, listen.

Listening—truly listening—takes some serious self-discipline. It definitely doesn’t come naturally. “Hey, all lives matter—including mine!”

But if I stop defending my rights long enough to listen to what others have to say, I hear things that are troubling.

We’re a nation with “free speech” rights, and we don’t seem to have a problem exercising those rights.

We do, however, have a problem listening to others when they exercise theirs.

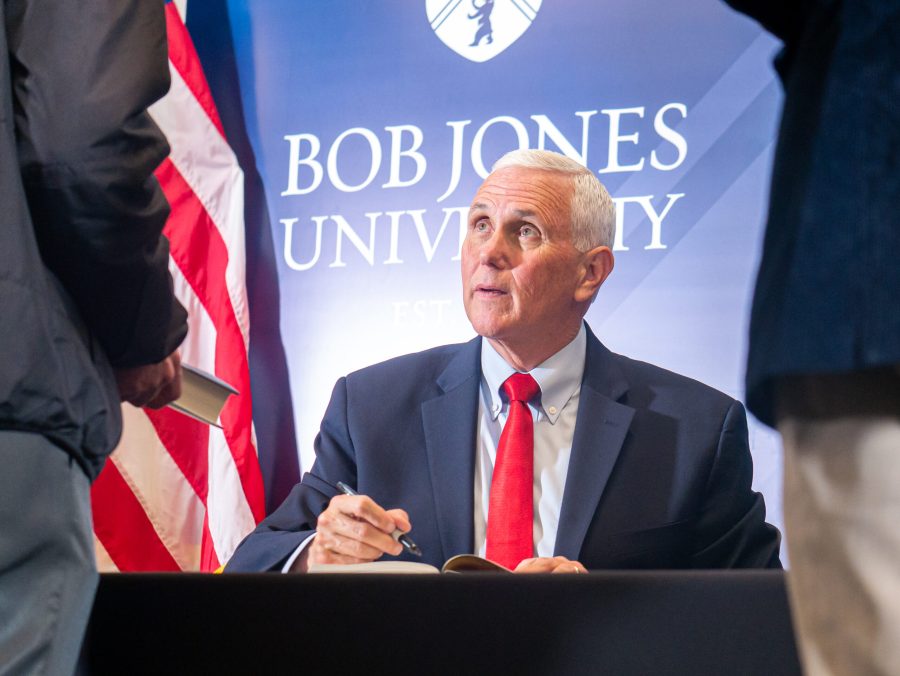

Candace Megerssa, a student at Killian Hills, recently won the High School Festival’s original oratory competition here at BJU with a provocative speech about race.

She gave statistics to show that African Americans are more often arrested, are more harshly punished and are more likely to have their crimes widely published than other American citizens.

Megerssa talked about racial stereotypes, such as Hollywood’s tendency to cast black people as gangsters, Hispanics as uneducated drug lords and Asians as socially awkward nerds.

She described how she was once ashamed of her own dark skin and kinky hair.

She spoke, movingly, transparently—and I listened.

After listening to her speech, Dr. Sam Horn sought her out on the Killian Hill bus and thanked her.

“I went on that bus because I was blessed by her courage, thankful for her graciousness, moved by her spirit, and convicted by her words,” he said.

Second, beyond listening, we need to feel.

Matt Mikalatos, regular host of the podcast “StoryMen,” wrote an article in response to the election results titled, “Why Donald Trump’s victory terrifies some of your ethnic minority friends.”

He said, “Many people of color are feeling that their voices will be minimized even further now.”

He’s right. An African-American lady at my church in Atlanta—whom I call “Mama Kay”—has become like family to me.

I asked her this week to share some of the fears she had regarding racism.

Here’s her answer: “Racism still exists, whether people choose to acknowledge it or not,” she said.

“Learning to empathize with those who have dealt with it from birth can bridge the gap that’s still evident between the races.

“More importantly, Christ has no favorites and heaven will not be segregated.”

Don’t argue. Breathe. Empathize. This is how a fellow citizen—a fellow Christian—feels. Accept it. Identify with it.

Now, I’m not saying that you have to concur with everything Mama Kay said—or everything I’m saying.

Empathy does not require agreement.

Mikalatos said, “You don’t even have to understand why [ethnic minorities] are afraid, or agree with their fears. But you can still express sorrow for their fear.”

My ethnic friends are sometimes afraid. And honestly, I both fear with and sorrow for them.

What might happen if my premed friend—who happens to be both black and a genius—gets pulled over?

What might happen if he’s at the wrong place at the wrong time?

Why does his mere entrance into a restaurant sometimes invite suspicious glances from others?

I don’t know the answers to those questions. But I can at least ask them, and I can be angry that I even have to wonder.

Our generation is good at talking. We’re social media natives and experts.

Talking is easy for us. Empathy? Not so much.

I invite you to work at it along with me. Hear your own words through the ears of others before you say them.

Recognize and reject stereotypes. Defend those who are being mistreated.

Leave no room for your friends—whatever their ethnicity—to doubt that you care or understand.

As Christians, we should love people from every race.

Revelation 7:9 tells us that in eternity there will be a great multitude of believers from “all nations, and kindreds, and people, and tongues,” standing before the throne.

Why not begin that harmony now?

As Mama Kay said, God hasn’t favored one people over another (Acts 10:34-35).

Instead, Galatians 3:27-28 teaches that the Gospel removes all boundaries so that Christians of every ethnicity and social background “are all one in Christ Jesus.”

Stop arguing for a moment. Listen. Feel. Empathize.